Fr. Matthew Mary | August 14, 2025

Today we celebrate the feast of St. Maximilian Kolbe, a Franciscan friar and martyr from the early 20th century. In his canonization homily in 1982, Pope St. John Paul II addressed the question of whether Maximilian Kolbe qualifies as a martyr. After all, he did give up his life—just not directly for the preservation of the faith. John Paul II answered this question clearly and decisively when he said:

“In judging the cause of Blessed Maximilian Kolbe even after his Beatification, it was necessary to take into consideration many voices of the People of God—especially of our Brothers in the episcopate of both Poland and Germany—who asked that Maximilian Kolbe be proclaimed as a martyr saint. Before the eloquence of the life and death of Blessed Maximilian, it is impossible not to recognize what seems to constitute the main and essential element of the sign given by God to the Church and the world in his death. Does not this death—faced spontaneously, for love of man—constitute a particular fulfillment of the words of Christ? Does not this death make Maximilian particularly like unto Christ—the Model of all Martyrs—who gives his own life on the Cross for his brethren? Does not this death possess a particular and penetrating eloquence for our age? Does not this death constitute a particularly authentic witness of the Church in the modern world?”

Pope John Paul II then invoked his apostolic authority to decree that Maximilian Kolbe would be venerated by the Church as a martyr.

Maximilian Kolbe was born Raymund Kolbe in Poland in 1894. As a young boy, he was known to be rather boisterous and temperamental. His mother prayed for him continually as she tried to manage her son’s behavior. Finally, in exasperation, she said to him, “What is to become of you?” These words struck him to his core. He went to Our Lady and asked her in prayer what would become of him.

He received a vision in which the Blessed Mother appeared to him holding two crowns in her hands—a red one and a white one—and invited him to choose between them. The red crown signified that he would give his life as a martyr, and the white crown signified perseverance in purity. He decided to accept both crowns. In 1907, at the age of 13, Raymund and his brother Francis decided to pursue a vocation as Franciscan friars. They illegally crossed the border from Poland into Austro-Hungary to enroll at the seminary for the Conventual Franciscans. A few years later, when he began the novitiate, he was given the religious name Maximilian.

Shortly after his ordination as a priest in 1918, he was in Rome when he witnessed angry protests conducted by the Freemasons against the Holy Father. With his strong devotion to Mary under the title of the Immaculata, he was motivated to defend the Blessed Mother and the Church from unjust attacks and to pray for the conversion of the Church’s enemies. He even desired to go to Japan to bring the Gospel there, and he established a Franciscan monastery on the outskirts of Nagasaki. Inspired by the Blessed Mother, he built the monastery in an unusual location. As it turned out, the monastery was completely spared when the United States dropped the atomic bomb on Nagasaki in 1945.

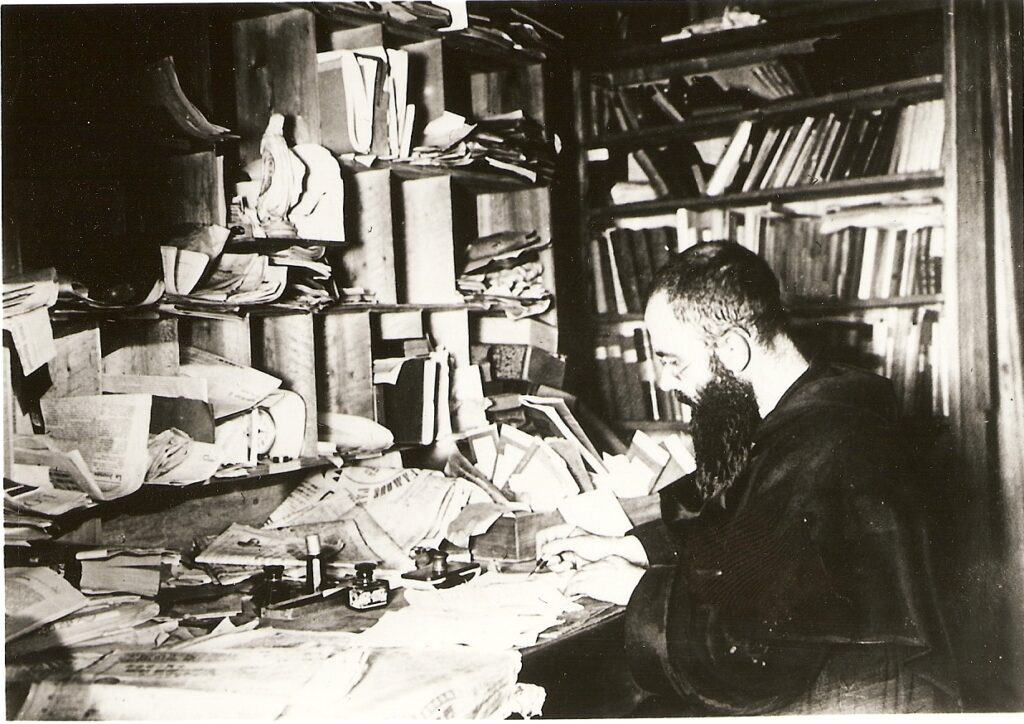

While still a seminarian, Maximilian had established the movement Militia Immaculata and recognized the immense potential to reach countless souls with the Gospel through modern means of communication. He founded a monthly periodical entitled Knight of the Immaculata and began construction of a radio station in 1938. The station was completed on December 8—the Feast of the Immaculate Conception—and became the first Catholic radio station in Poland. St. Maximilian had plans to use both television and radio for evangelization. Unfortunately, he never had the chance to launch these initiatives, as he was arrested by the Nazis in 1941 and sent to the Auschwitz concentration camp.

One can only imagine the horrors that people witnessed in the concentration camps, especially at Auschwitz. St. Maximilian was forced into hard labor, carrying heavy stones for the construction of the crematorium wall. He was brutally beaten by guards, who even set dogs on him. Yet he bore these injustices with grace and serenity. He never retaliated, cursed, or spewed hatred. Instead, he recalled the words of Christ about loving one’s enemies and prayed for his persecutors.

He resisted the temptation to fight over scraps of food, even sharing what little he had. He heard confessions and encouraged his fellow prisoners to unite their sufferings with Christ’s Cross. He told them:

“Let us not forget that Jesus not only suffered, but also rose in glory; so, too, we go to the glory of the Resurrection by way of suffering and the Cross.”

In July 1941, after a prisoner escaped, the deputy camp commander selected ten men to be starved to death as punishment. One of them, Franciszek Gajowniczek, cried out, “I pity my wife and my children!” St. Maximilian stepped forward and offered his life in exchange for the man with a family. The commander accepted his offer. Gajowniczek was later transferred to another camp, liberated by the Allies, and lived until 1995, dying at the age of 93.

Ordinarily, prisoners condemned to the starvation bunker would lash out in desperation. However, when St. Maximilian and nine others were stripped naked and locked inside, he encouraged them to pray and sing hymns. Instead of hearing curses and cries, the guards heard Marian hymns and prayers. Maximilian helped his fellow prisoners die well in the grace of Christ.

Two weeks later, Maximilian was one of the last survivors. The guards ended their lives with injections of carbolic acid. This is one reason why St. Maximilian is regarded as the patron saint of drug addicts.

St. Maximilian Kolbe is remembered for his undying love for the Blessed Mother, his devotion to the Catholic faith, and his zeal for evangelization. He not only preached the faith but lived it daily through loving action. Even in one of history’s darkest places, he became a bright light. Some Nazi soldiers even recognized that there was something extraordinary about him.

The Church holds up his life as an example of heroic virtue—a reminder that, even in the most dire circumstances, the virtues of faith, hope, and charity can shine. Like St. Maximilian, all Christians are called to be lights in a dark world, so that the darkness of sin may be overcome by the light of God’s grace, love, and mercy.

I am a Secular Franciscan and want to know about more about Franciscan life.