July 29, 2025

For those familiar with the classic sitcom Seinfeld, there’s a scene—and an ongoing theme—in the show where George Costanza and his wild-eyed father, Frank, faced with stress, irritation, and anxiety (generally brought on by each other), scream, “Serenity now!” It’s both dramatic and very funny, and like all good comedy, it can and does contain a kernel of truth—even a launching point for some interior reflection.

With that in mind, perhaps George and Frank Costanza may have been better served by screaming, “Genesis now!” Hmmm… Let’s launch ourselves into a deeper reflection by setting aside this comedic episode for the time being and turning to a scriptural gem from the very first chapter of the Book of Genesis:

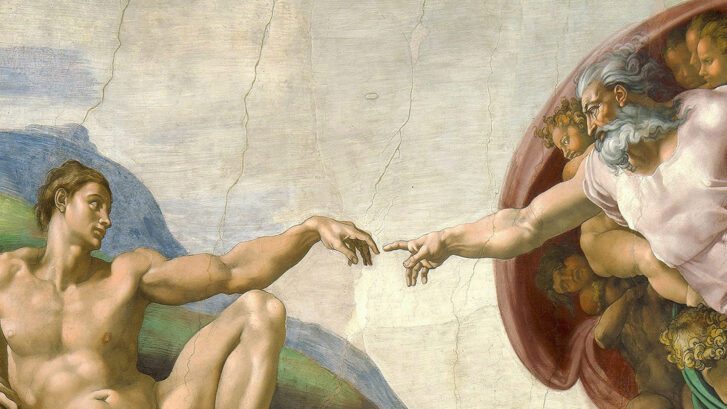

Then God said: “Let us make man in our image, after our likeness…”

God created man in His image; in the divine image He created him;

male and female He created them…

God looked at everything He had made, and He found it very good…

Perhaps no other passage in Sacred Scripture more clearly captures the essence of man’s inherent—and ultimately transcendent—human dignity than this narrative from Genesis. In a particular way, this concept was reflected early on in the pontificate of now Pope St. John Paul II when, in a letter to then–United Nations Secretary-General Kurt Waldheim, he offered his answer to the central political question of the modern era:

“What basis can we offer as the soil in which individual and social rights may grow?”

Our now canonized Holy Father replied as follows:

“Unquestionably, that basis is the dignity of the human person.”

Interestingly, our dearly departed Pope Benedict XVI and Pope Francis each uniquely echoed that very theme during their own pontificates.

To adequately grasp the full depth of Pope St. John Paul II’s understanding of the dignity and uniqueness of the human person would require not only a close reading of his many papal encyclicals and apostolic letters (notably, his first encyclical, Redemptor Hominis), but also his pre-papal philosophical writings and plays penned under his baptismal name, Karol Wojtyła. Moreover, one would also be bound to study John Paul’s entire life—particularly his years as a young Polish cardinal who, during the Second Vatican Council, helped influence and shape one of the most celebrated council documents, Gaudium et Spes, especially the first chapter entitled “The Dignity of the Human Person.” This, however, would be a daunting task—perhaps even a lifetime project—and certainly beyond our scope here and now.

Given all of the above—and the trite but sadly somewhat true axiom that “there is nothing less read than an encyclical of a deceased pope”—we’ll limit ourselves to a few semi-salient points, beginning with a brief look at The Christian Personalism of John Paul II, written by Fr. Ronald D. Lawler, O.F.M. Cap. Broadly speaking, this Personalism is our guide. Our reflection also presupposes the backdrop of Pope John Paul II’s experience in German-occupied Poland, for it was then that the young Karol Wojtyła began to formulate and deeply reflect on this vision of man—of what man was intended to be at creation.

Fr. Lawler’s analysis of what has come to be known as the Personalism of John Paul II largely focuses on the concept of the dignity of the human person. When discussing man’s inherent dignity, the transcendent worth of the individual person is of central importance not only to those of us who claim to be Christians, but to all people of goodwill and to any culture that hopes to remain truly and authentically human. Sadly, our current age in particular seems, on one hand, to endlessly banter on about its respect for the human person—constantly formulating human rights with great zeal and incessantly proclaiming that each person is “endowed with inalienable rights.” Yet at the same time, our culture is obviously skeptical about each man’s transcendent value, as is tragically confirmed by the continued annihilation of the unborn—the most defenseless of human persons—the growing disregard for the elderly, the infirm, the poor, and genuine foreign nationals, not to mention the increasing number of souls suffering from various forms of dysphoria, and so on. We live in an age that has not only inordinately exalted and glorified, but also purposefully humiliated and crushed the human spirit. The divide is palpable.

St. John Paul II was prophetic—uniquely aware of this—having heard the desperate screams of people systematically targeted and rounded up in Gestapo raids. Karol Wojtyła undoubtedly heard the cries and felt the despair from the prison-like ghettos near his own Debniki Square in Kraków; and he knew directly from Cardinal Adam Stefan Sapieha, Archbishop of Kraków from 1911 until his death in 1951, of the grisly inhumanities at Auschwitz. Clearly, as a poet, playwright, professor, priest, and now canonized pope, he deeply sensed that there is an inherent dignity in man—whether in the concentration camps of the Nazis or in the various other means of dehumanization that threaten man through corrupt ideologies in both East and West.

Where, precisely, is this dignity of man revealed to man? To answer this, we turn again to the Second Vatican Council document Gaudium et Spes, which reaffirms both the contradictory views man puts forward about himself and the transcendency of man as revealed in the Genesis narrative. The Council Fathers, influenced by Cardinal Wojtyła, gave us a concise explanation with clear and proper reasoning:

“Deep within his conscience man discovers a law which he has not laid upon himself but which he must obey. Its voice, ever calling him to love and to do what is good and to avoid evil, tells him inwardly at the right moment: do this, shun that. For man has in his heart a law inscribed by God. His dignity lies in observing this law…”

Throughout his analysis of man, then-Cardinal Wojtyła demonstrates that, although he is deeply familiar with the many philosophical ways of thinking about man, even the classical scholastic Christian definitions fall short. Somehow, an “individual subsisting in a rational nature” or a “body-and-soul composite” does not fully express the richness of the human person. Too detached? Too clinical? Perhaps. Instead (or in addition), Christian Personalism views the person as a distinct reality—the ultimate possessor of a nature that uniquely mirrors God Himself. Man possesses an intelligence capable of knowing and intentionally becoming all things; he has a will, the capacity to love, and the ability to relate himself to each person he encounters. Here we catch a glimpse of the at-times enigmatic nature of Personalism.

The culmination of John Paul II’s thought on the revelation of man is found in his first encyclical, Redemptor Hominis, issued in April 1979. There, the sainted pope presents the full range of his teaching on the inherent dignity of man: namely, that it is only in the mystery of the Word made flesh that the mystery of man becomes truly understandable. By His Incarnation, Jesus Christ, the Son of God, has, in a certain way, united Himself with each person. It is humanity that is elevated in God’s earthly birth. Humanity—human “nature”—is taken into the unity of the divine person of the Son. Therefore, the birth of the Incarnate Word is truly the beginning of a new power for humanity itself. It is by reason of the Incarnation that:

“…man in all the fullness of the mystery in which he has become a sharer in Jesus Christ, the mystery in which each one of the four thousand million human beings living on our planet has become a sharer from the moment he is conceived beneath the heart of his mother…Christ is in a way united even when man is unaware of it…”

What St. John Paul II was saying is that Jesus Christ is not only the fullness of the revelation of God and His salvific will for all mankind, but also a revelation of who man is—of what man was intended to be at creation, by reason of the Incarnation. Thus, man possesses not just an inherent worldly dignity randomly assigned by competing political ideologies, but an inherently transcendent and infinite dignity.

What cannot be overlooked is the joy one senses when reading Pope John Paul II’s writings—or when recalling his own joyful disposition and the profound dignity he lived out to the very end. A testimony to hope, and to his conviction regarding Christian Personalism. As mentioned earlier, it is no surprise that John Paul II emphasized this particular quality of man—his inherent, transcendent dignity. After all, as the “Polish Pontiff,” John Paul II the Great brought to the Bark of Peter the experience of a man who was an underground seminarian under Nazi rule; a Church leader under Marxist Soviet domination; a sportsman and mystic, playwright, poet, philosopher, theologian, professor, and—perhaps most importantly—a priest and pope. He carefully cultivated and arduously reflected upon an intellectual and spiritual answer to both the reality and mystery of man. Let us not forget that this understanding of Christian Personalism was reflected not only in his philosophical and theological works, but in his dramas, poems, encyclicals, talks, and most of all, in the witness of his life—especially in his suffering. Not unlike Pope Francis, he met with paupers, princes, and people of every sort and condition—always encountering not mere men, but the eternal focal point of the human drama: Jesus Christ.

In closing, let’s reflect on an excerpt from a homily delivered by Pope John Paul II on October 7, 1979, in Washington, D.C. It seems to encapsulate the whole of reality for man—that is, true Christianity:

“I do not hesitate to proclaim before you and before the world that all human life… is sacred, because human life is created in the image and likeness of God. Nothing surpasses the greatness or dignity of a human person. Human life is not just an idea or an abstraction; human life is the concrete reality of a being that lives, that acts, that grows, and develops; human life is the concrete reality of a being that is capable of love and service to humanity.”

The profundity of this statement is immense and deeply revealing. His words still can—and must—have a healing effect, whereby we no longer look at the perpetually agitated—the social media influencers, podcasters, pundits, politicians, etc.—with condescension, anger, or rage. Rather, we look at one another with mutual compassion, sorrow, and mercy. Why? Because, whether the ever-growing group of dissenters against humanity realizes it or not, they too are created with an inherently infinite dignity.

The question is: Will they—will we—ever come to know it?

Genesis Now!